Russ Yarrow

Business will be a big voice in Twitter’s future direction

At the Dialogue Project, an important new initiative at Duke University where I serve as an advisor and a member of the project’s Steering Committee, our premise is ambitious and straightforward. We believe business can and does play a constructive role in lowering the level of polarization in America and promoting more civil dialogue.

Business has all the ingredients to make a difference. It enjoys a high level of trust among the public, exerts tremendous influence through its spending and investments, and has made conflict resolution into a discipline. After all, when you run a company like General Motors you want to be sure your workforce is aligned and working toward the same goals, regardless of personal differences.

An example of how business effectively bridged the chasm of a polarizing issues is same-sex marriage. In the early 2000s, the issue of gay marriage was a political football being punted endlessly back and forth. While Barack Obama was running for president it became something of a parlor game to figure out his position — was he or wasn’t he?

Meanwhile, the business community was already on the bus. By 2012, when Obama became the first president to support same-sex marriage, the business community had already embraced it. A 2010 Mercer survey of about 3,000 companies found that domestic-partner benefits were already being offered by 72 percent of companies employing more than 20,000 people.

Why was business leading on this issue? It wasn’t so much a moral decision for businesses, but a pragmatic one. Recruiting and retaining talent is essential for sustained business success, and limiting extended health benefits to traditional marriages simply limited the talent pool. Of course, expanding benefits to domestic partners also lined up with evolving attitudes on equality, human rights and related social issues.

The point is that business didn’t wait to be led on the issue — it led the issue.

When business engages with social issues, of course, it doesn’t always come out on the right side. For instance, the Walt Disney Co. made some missteps earlier this year around a new Florida state law — the Parental Rights in Education act, or the “Don’t Say Gay” law — which created a controversy that swirled for months. Despite having reached an accord with LGBTQ stakeholders, Disney drew the wrath of Florida elected officials, who retaliated by abolishing the special tax district where the company’s theme park is located. That impasse still has not been resolved.

So it’s interesting to watch the dance going on between Elon Musk and advertisers on Twitter (which is essentially a one-man show since Musk’s acquisition). It’s a real-time case study of how business wrestles with a “third rail” issue.

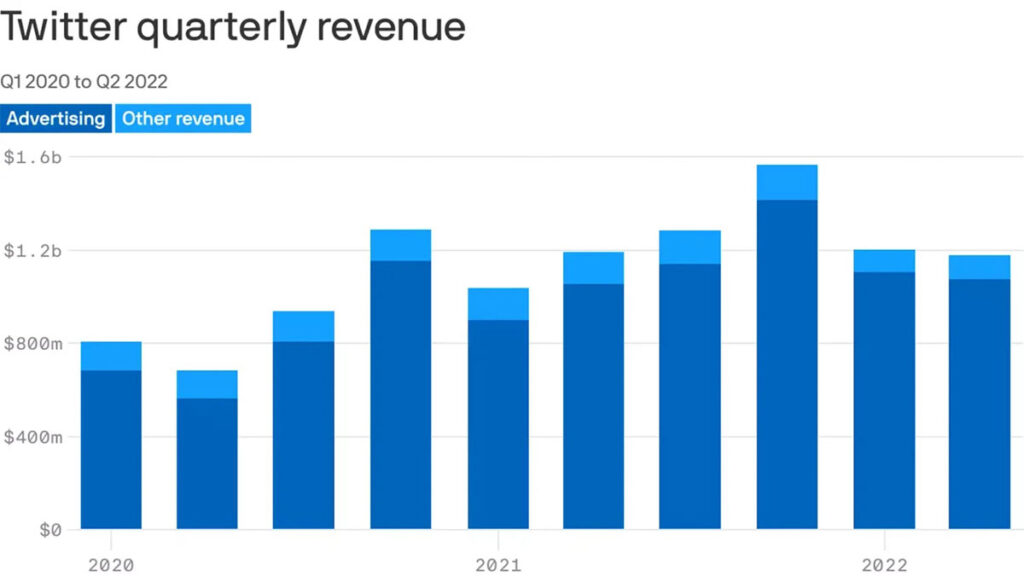

At this point, while Musk tries to navigate all the complexities of his acquisition — content moderation, revenue, employee relations, to name a few — business is flexing its muscle. And it’s a big muscle — about 90 percent of Twitter’s $5 billion of revenue in 2021 was from advertising.

General Motors, Pfizer and Audi are some of the advertisers who have left Twitter for the moment, or are considering doing so. One advertising executive, speaking to the Financial Times, called it “quiet quitting.” There hasn’t been any grandstanding. GM released a statement that read, “As is normal course of business with a significant change in a media platform, we have temporarily paused our paid advertising.” Advertising agency Interpublic Group is also advising its clients to sit on the sidelines while the Twitter transition sorts itself out.

Still, the subtext is clear. While advertisers have referenced the “uncertainty” of Twitter’s governance and strategies going forward, business is also concerned about the potential for Twitter to turn toward more of an unbridled, anything-goes platform on which disinformation can flourish.

For instance, the use of a racial slur on Twitter increased by almost 500% in a 12-hour period over the previous average following Musk’s acquisition, according to the Princeton-based Network Contagion Research Institute, which tracks “cyber-social threats.” Twitter attributed the surge to a trolling campaign traced back to 300 inauthentic accounts.

“Twitter’s policies haven’t changed. Hateful conduct has no place here. And we’re taking steps to put a stop to an organized effort to make people think we have,” Yoel Roth, Twitter’s head of Safety and Integrity, said. Trolls or not, this kind of eruption did little to calm advertisers.

It’s not clear if Musk will develop an alternative revenue stream to advertising — or even if that’s possible. Selling blue checks for $8 clearly isn’t going to do it, and cutting the workforce in half is an expense strategy, not a revenue plan. Maybe a subscription model? Only Elon knows at this point. But an informed guess is that advertising will be necessary if Twitter doesn’t want to devolve into a niche product. TikTok’s phenomenal growth, for instance, is being driven by advertising, which totaled $4 billion in 2021 and is expected to reach $12 billion this year.

At this point, business clearly isn’t dictating terms to Twitter; it’s simply registering concerns about the potential direction that the platform might take. But just by simply raising those concerns — and withholding millions of dollars in advertising in the meantime — business is having an influence.

I wouldn’t be surprised if, in addition to “quiet quitting,” there’s also some “quiet influencing” going on. Businesses may not be making public statements about Twitter, but it’s probably safe to assume that advertisers are letting Twitter know through informal channels what it expects of Twitter going forward. As a former brand manager for a Fortune 10 company, I can tell you I would have been eager to share those expectations.

I can imagine the conversation going something like this: “Look, I’m sure Elon has some great ideas for Twitter, but we will tell you that if it trends toward a platform where trolling, disinformation, conflict and bullying are allowed, or where civil dialogue isn’t allowed, we’re gone. Our company values trust, respect and truth. If those aren’t values for Twitter going forward, we’ll find other places to spend our advertising dollars.”

It’s hard to say how all this will turn out, but you can be sure that business is doing what it can right now to steer it in the right direction. Stay tuned.